What is Creatine?

It is a substance produced by our kidneys and transported to the liver, eventually stored at skeletal muscle. Creatine (CR) naturally helps muscle contractions, regulated by adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the compound required for each muscle cell action. ATP uses CR to restore function, so the dogma indicates that the volume of CR within muscle cells will impact the amount of energy generated during a short period of high intensity physical activity (6-8 seconds at a time) (4). CR has been mainly used for performance enhancement during heavy lifting, or high intensity activities that require forceful, anaerobic energy. The usage of CR as a supplement became popular in the early 90’s, after some British, Olympic gold medalists admitted using creatine, after the Barcelona games in 1992. The average CR pool in a 70kg (154.3 lbs.) male is 120-140 g, depending on muscle mass and muscle fiber type (2).

Creatine supplementation possible benefits

Creatine supplementation could be useful accelerating the process of restoring available ATP, with possible enhancement of high intensity activity, such as lifting something heavy, in the short term (6-8 seconds).

Strength and Power.- During a review of 53 scientific studies on upper body strength (6), and the review of 60 studies on lower body strength (5) concluded that CR supplementation is effective in strength performance, in exercises shorter than 3 minutes, and regardless of training status (sedentary, recreational or competitive individuals), training protocol (strength, aerobic, or concurrent training) and CR dosage. Moreover, another study (9) concluded CR supplementation enhanced power output maintenance during maximum effort exercise, with rest of 30s between sets. CR has demonstrated its buffering capabilities of lactate and hydrogen ions, which cause a decrease in blood pH levels and subsequent fatigue. Thus, creatine is recognized as a performance enhancer (4).

Endurance Exercise. – Results of the usage of CR in endurance athletes have shown mixed results, but the evidence is favorable to studies proving no effect of the supplement on endurance events (4).

Creatine Supplementation: before or after training?

During a study with recreational body builders, the effects of 5g of CR. before or after training were measured, in relationship to Bench Press (1RM) and body composition. The results showed more benefit on the post-workout group (1).

Foods that contain Creatine

Most creatine containing food items come from animal sources. The following table shows some of the food items with higher concentrations of CR (8):

| Food Source | Serving | Creatine Content (g) |

| Herring | 225g/8oz | 2.0- 4.0 |

| Pork | 225g/8oz | 1.5- 2.5 |

| Salmon | 225g/8oz | 1.5- 2.5 |

| Beef (lean) | 225g/8oz | 1.5- 2.5 |

| Milk (1% Fat) | 250 ml/8oz | 0.05 |

We should consider the increase on the consumption of naturally available CR not only impractical, but potentially detrimental for performance enhancement. The consumption of a great amount of these food items would be needed to fulfill the creatine dietary recommendations (5 g/per day). Meanwhile, protein and fat consumption would be easily exceeded and most likely, contraindicated. For these reasons, CR supplementation is often an obvious choice by an athlete (8).

Creatine usage risk and limitations

The demand for CR in our body is met both by diet and endogenous production (the amount that our body produces). However, research has shown that the amount produced by the body is dependable on how much we obtain from our diet, including supplementation. In other words, if we obtain CR in excess from diet and supplementation, our body reduces its production. Obviously, the intent of supplementation is to increase CR levels. Maximum increase in CR levels has been recorded about at about 20%, after a high dosage program (3).

Excessive CR supplementation (>30g per day), results in cell saturation and consequently on the waste of the excessive CR, via kidney filtration. This process could add unnecessary stress to the kidneys and could be detrimental. Nevertheless, there are many studies that examined the effects of CR supplementation on renal function with no negative effects recorded (4). Furthermore, after supplementation ceases, regular, pre-supplementation CR levels return to normality after about 30 days.

Even though it has been argued that creatine affects thermoregulation during heat conditions, in a study review (7) concluded there is no evidence that CR negatively affect our body’s ability to regulate temperature, nor affects an athlete’s body fluid balance, when the supplement follows proper dosages.

Conclusion:

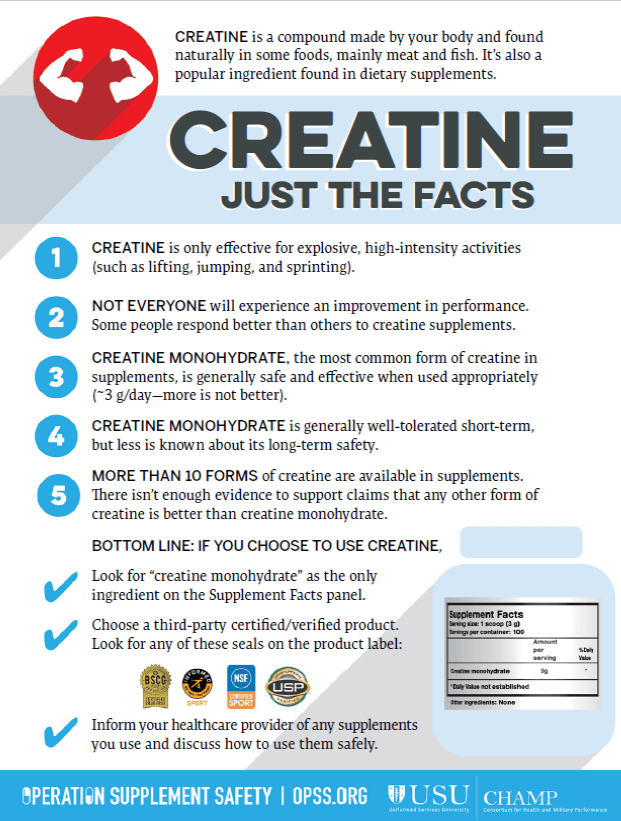

In addition, the Operations Safety System (OPSS), communicates the following warning:

“Creatine (Phosphocreatine, creatine monohydrate) Warning: During creatine supplementation, water intake should be >64 ounces per day and sufficient to maintain proper hydration level. Creatine functions by drawing water from the rest of the body and holding it in the muscles. During creatine use, the drink to drink more water than normal is needed. Some individuals may experience gastrointestinal symptoms, including loss of appetite, stomach discomfort, diarrhea, or nausea. Diabetes medications, acetaminophen, and diuretics may have interactions with creatine and should not be used together. Taking caffeine with creatine could increase the risk of side effects.

Grounding: 24-hour local grounding after first dose and if experiencing GI symptoms.”

References:

2. Brosnan, J.T., da Silva, R.P., Brosnan, M.E. (2011). The metabolic burden of creatine synthesis. Amino acids 40: 1325-1331.

3. Cooper R., Naclerio, F., Allgrove, J., Jimenez, A. (2012). Creatine supplementation with specific view to exercise/sports performance: an update. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 9: 33.

4. Dorrell, H., Gee, T., & Middleton, G. (2016). An update on effects of creatine supplementation on performance: a review. Sports Nutrition and Therapy, 1(1), e107-e107.

5. Lanhers, C., Pereira, B., Naughton, G., Trousselard, M., Lesage, F. X., & Dutheil, F. (2015). Creatine supplementation and lower limb strength performance: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Sports Medicine, 45(9), 1285-1294.

6. Lanhers, C., Pereira, B., Naughton, G., Trousselard, M., Lesage, F. X., & Dutheil, F. (2017). Creatine supplementation and upper limb strength performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports medicine, 47(1), 163-173.

7. Lopez, R.M., Casa, D.J., McDermott, B.P., Ganio, M.S., Armstrong, L.E., Maresh, C.M. (2009). Does creatine supplementation hinder exercise heat tolerance or hydration status? A systematic review with meta-analyses. J Athl Train. 44(2):215‐223. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.215.

8. Tarnopolsky, M.A. (2010). Caffeine and creatine use in sport. Ann Nutr Metab 57: 1-8.

9. Yquel, R.J., Arsac, L.M., Thiaudiere, E., Canioni, P., Manier, G. (2002). Effect of creatine supplementation on phosphocreatine resynthesis, inorganic phosphate accumulation and pH during intermittent maximal exercise. Journal of Sports Sciences. 20: 427-438.