The intention of this article is to share my own experience in hopes that others would make a better choice, in comparison to mine. This is when the old saying, “live and learn” fits like a glove as I share this with you.

My career as an athlete started when I was 5, playing football. I took it very seriously. When I was 15 years old, my dad took me to a gym and hired a personal trainer for me. I already had a good idea of how to weight train, but this trainer was great and taught me so much. It was a great experience. Since then, weight training became enjoyable and more familiar. Throughout the years, it became a regular practice as I continued my preparation as a football player. However, I never thought about something very important; I was trained by a body builder, who wanted me to become a body builder and who did not have any idea of energy systems and the requirements of a football player, when it came to training. Regardless, I do not think he cared either (not his fault, for back then, there was extremely limited research about training athletes). Back then, most football players, including the NFL followed body building “workouts” to get massive, but they never trained the way they should have, because they did not know any other way.

If you think about it, it would not be fair to compare body composition and performance (speed, agility, strength, power, endurance) of athletes who played any sport in the past, with the current athletes. During a master’s thesis study (2), a significant difference was found between collegiate football players who participated in 1987 or 2000, as vertical jump, squat, and power records were significantly greater for the latter. Data was compared by position; for example, 2000’s Defensive Linemen were 10.8%, 9%, and 6.9% better in power, vertical jump and squat, when compared to their antecessors from 1987. Linebackers shown a decrease of 15.5% in body fat, and an increase of 12.5% and 7.3% on vertical jump, and power. Defensive Backs records shown a 20.9% lower body fat, and improvements of 10% and 7.9% on vertical jump and power, respectively (2). Such records exemplify the influence of scientific and practical advances in the strength and conditioning field, as athletes are better prepared, year after year. This applies to every other sport or specialty, and tactical athletes are no different to any other athlete!

Going back to my experience, on my first year as a collegiate football player, despite having access to our team’s strength and conditioning coach, I decided to take on my own off-season strength and conditioning training. After all, I thought I had enough experience in the gym, so I “did not require a coach.” After looking at the coach’s program, I decided it did not make sense to include Olympic lifts, such as power cleans. After all, I thought “I am a football player, not a weightlifter.” It was important for me to get bigger and stronger and thought Olympic lifts were not appropriate for my purposes. Thus, I continued my own “routine.” As pre-season started, I had already injured both of my hamstrings. I did not understand why, for I was squatting decent numbers. The reality was, I had good knowledge of how to exercise (technique wise) but had no idea about the rationale behind a strength and conditioning program. I was simply working hard, but not smart. My strength improved because I was dedicated. But after a while, I hit a plateau. Consistent exercise will always have benefits, during the early stages, as we gain adaptations on the nervous system. Later, if volume of training is substantial, strength and hypertrophy would occur, but without a proper progression, a plateau is imminent. In many cases, injuries occur due to overuse of certain muscles and connective tissue and muscle imbalances take place, due to inadequate exercise prescription and programming. But I was convinced I did not need a coach, then; and I was wrong all along. I should have listened and followed my coach’s program.

A good strength and conditioning program is designed based on an athlete’s performance requirements and the calendar of competition. The program should be scheduled in multiple, progressive phases, which build on top of each other. Each phase progresses from the previous, varying in volume, intensity, frequency and exercise order and selection; year after year, there should be a progression. That is how you could see a freshman wide receiver, weighting 175 lbs., squatting 225 lbs., and running a 4.6 s, 40 yard dash; and, the same player, as a senior, weighting 210 lbs., squatting 435 lbs., and running a 4.2 s 40 yard dash. Notwithstanding, that is 4 years of progressive, ongoing, properly programmed, strength and conditioning training. As another example, I mention one of my tennis athletes at UCF. As a senior, during off-season testing, he recorded a 225 lbs. squat, 1RM. He used to say he was not a “fan” of weightlifting, because he thought that would make him bulky and slower on the court. After 6 months of strength and conditioning training, he had increased his body mass significantly and I spotted him during his 1RM, as he lifted 435 lbs. Then, he used to talk about how much “lighter” he felt on the court. Isn’t it logical to assume that when you are able to handle greater external resistance (weights), your own body weight would be easier to handle?

The reality was that my tennis players along with any other team we trained at UCF, always followed a periodized, progressive program to ensure proper adaptations, recovery and ongoing performance enhancement. But nothing would happen without the discipline and adherence to a specific program, designed for their sport requirements.

Periodization models vary significantly in exercise selection and volume, and research has shown that undulating periodization is the most effective for maximum strength (1), making volume and intensity increase, decrease and increase again, in a gradual, weekly or daily, manner to allow for proper recovery and avoid plateaus.

The whole purpose of this long, boring story is to share how much I wish I would have listened to my strength coach in college. Designing an effective and efficient strength and conditioning program not only requires of your practical experience as an athlete, or weightlifter. It involves many different variables to be considered (exercise splits, exercise selection, order, volume, intensity, rest periods, frequency, tempo, resistance type, plane of motion), and all of these variables should be defined in consideration to the type of athlete, and based on scientific evidence.

With the excessive access to fitness information these days, it is easy to get excited about heavily marketed fitness trends. However, none of those programs would be able to fit you in a month to month, and year to year basis. The ideal model should be a gradual, month to month, phase to phase progression to ensure each phase builds on the previous, avoiding interference of one program with another. Commercial programs have no long-term progression and usually profit from a short trend, created by their marketing success. However, it is fair to say that any program is better than no program. In the end, not everybody has access to a strength and conditioning coach, except for some lucky high school athletes, some DII and DIII colleges, and of course, all DI and professional athletes.

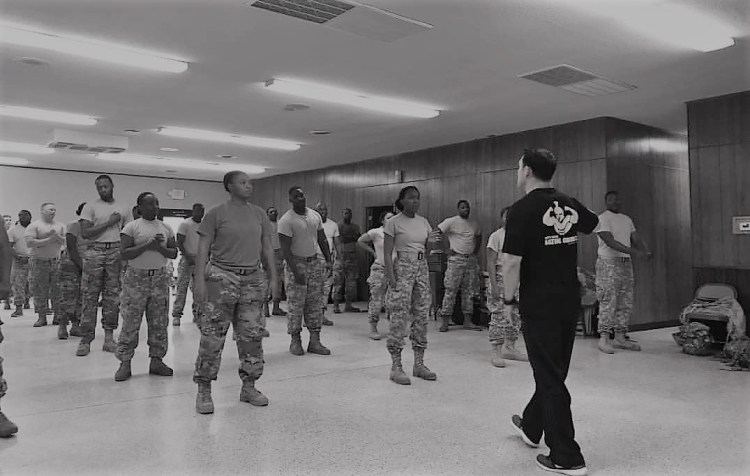

My question has always been, if elite athletes (DI and professional) are the most talented, competitive and in highest pursue of excellence, yet still need a strength coach; why wouldn’t you take advantage of the services and support of a strength coach, when you are a tactical athlete? What makes you different than a professional athlete?

As a tactical athlete, you depend on your mental and physical health to train and to perform your job. You are meant to maintain and endure a very demanding career as the elite airman you decided to become. Your ongoing preparation never ends, and your level of readiness do not only affect you, but your fellow airmen. If we all think that way, we would start by saying, “I take care of myself first, so I can take care of others who depend on me.” We will then achieve the best level of readiness and dependability. We will reach our greatest capacity as individuals and as a team.

With sincere appreciation,

Coach Fernando

References:

Caldas, L., et al. (2016). Traditional vs. Undulating Periodization in the Context of Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Sports Science 2016, 6(6): 219-229.

Secora, C.A. (2002). A comparison of physical and performance characteristics of NCAA Division I football players: 1987 and 2000. Student work. 863. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/863